The European Commission is proposing to ban two fungicides and one insecticide due to their high toxicity to human health and the environment. This ban is good news for human health and the environment, but it took far too long. In accordance with the Pesticide Regulation, Dimoxystrobin and Oxamyl should have been banned in 2016 and Ipconazole in 2018. This article looks at some of the current flaws in the implementation of the Regulation that extends the lifetime in European fields and plates of very toxic substances.

The Commission submitted to the Member States its proposal to ban three pesticide substances: Dimoxystrobin, Ipconazole and Oxamyl. The three are “candidates for substitution”, the list of most hazardous substances in the EU under the Pesticide Regulation. The fungicides Dimoxystrobin and Ipconazole are also part of the “Toxic 12”, pesticides that should be banned immediately according to PAN Europe.

Dimoxystrobin and Oxamyl have been authorised in the EU since 2006. Ipconazole was introduced in 2014, and all are being used by farmers in a majority of Member States for many years. For the time being, it seems that a number of Member States support the ban on Dimoxystrobin and Oxamyl, while the uncertainty remains for Ipconazole. If adopted by Member States, these bans will thus mark a step towards a total phase-out of the most hazardous pesticides in the EU by 2030 as demanded by more than 1.1 million European citizens in the ECI Save Bees and Farmers.

This is about time, for they are also a clear reminder that synthetic pesticides can be particularly harmful. Not just for “pests',' but also for unborn children, consumers, bees or aquatic species. Hence the crucial role of the Pesticide Regulation that puts the protection of human health and the environment above the interests of agribusiness and the market. The problem is that both the European Commission and Member States apply this regulation very badly. The result is that people and the environment are exposed to substances that have harmful effects which should have been avoided.

Dimoxystrobin and Oxamyl: 17-year approval without reassessment due to systematic prolongations

Both Dimoxystrobin and Oxamyl are substances whose approval period has been continuously extended, without more recent scientific assessment than the ones performed in 2006. Initially, both substances’ approvals were due to expire in 2016 after a 10-year period. The renewal process is designed so that a decision on their renewal must have been taken by 2016, building on an assessment of recent scientific knowledge. The file should be prepared by one or several appointed Member State(s) (1).

However, the practice is not in line with the Regulation First, Dimoxystrobin and Oxamyl approval were prolonged for a year and a half due to the introduction of new regulatory requirements. Next, they were both prolonged 6 times for a year. This extended their approval period to a total of 17 years, without the necessary assessment. The reason? The Member State(s) in charge of reassessing the substances did not deliver their conclusions to the European Food Security Agency (EFSA) on time limits set out in the Regulation. These delays are increasingly common and the systemic reaction from the European Commission is to close its eyes by prolonging the substances’ approval. With time, the situation got worse: almost all substances identified as “candidates for substitution” are now subject to one or more prolongations of their approval period (See our Factsheet Patterns of systematic and unlawful prolongation of toxic pesticide approvals). PAN Europe has lodged a complaint to the EU Court of Justice to stop these practices.

If the rules had been respected, Dimoxystrobin and Oxamyl would have been banned in 2016, based on the scientific conclusions of recent research. The delays in risk assessment by Member States and the Commission’s standard reaction of annually prolonging the approval are not acceptable. The unlawful prolongations put human health and the environment at great risk. This is contrary to what is required in the Pesticide Regulation.

Ipconazole: a substance which does not meet the approval criteria since 2018

In March 2018, the European Chemical Agency (ECHA) concluded that Ipconazole is damaging the development of unborn children and classified it as presumed toxic to reproduction (Cat. 1B). In accordance with the Pesticide Regulation, these properties are so toxic that any exposure to the substance poses an unacceptable level of risk to humans and the environment. Therefore, this classification must lead to an immediate ban on the substance.

In practice, it took the Commission four years to finally propose a ban. It will take even longer for it to be adopted by Member States and become effective (6-month grace period). The main reason for that is that first, the Commission has to proceed with an approval review, which it did no sooner than 2021. Then, the pesticide industry holding Ipconazole’s approval licence asked the Commission to assess whether human exposure to Ipconazole could be “negligible” in some specific use conditions. Negligible exposure means no contact with humans according to the Regulation. The European Commission is well aware that there is no record of possible negligible exposure by EFSA for any pesticides substance so far. But the move gave the industry a few more years of marketing Ipconazole in Europe. Indeed, EFSA had to carry out an additional assessment which took months. This trick is now used every time and very disappointingly, the European Commission played the game of the industry instead of proposing immediately a ban.

This approach is contrary to the Regulation and the precautionary principle underpinning it and benefits only the pesticide industry. A recent judgement of the European Court of Justice made this very clear:

“In that regard, it should be borne in mind that those provisions are based on the precautionary principle, which is one of the bases of the policy of a high level of protection pursued by the European Union in the field of the environment, in accordance with the first subparagraph of Article 191(2) TFEU, in order to prevent active substances or products placed on the market from harming human or animal health or the environment.” Followed by: “Furthermore, it is clear, as stated in recital 24 of Regulation No 1107/2009, that the provisions governing authorisations must ensure a high standard of protection and that, in particular, when granting authorisations of plant protection products, the objective of protecting human and animal health and the environment should ‘take priority’ over the objective of improving plant production.” (recitals 47 and 48).

When a substance like Ipconazole does not comply with the health and environmental safety requirements of the Regulation, the Commission should immediately ban it. This process should not be delayed by an assessment of unlikely possibilities of negligible exposure, which should be assessed after.

No substitutions as required by European law

Citizens and the environment would at least have been partly protected from Dimoxystrobin, Ipconazole and Oxamyl if another aspect of the regulation had been respected. As pointed out earlier, the three substances belong to the regulatory category of “candidates for substitution”. It means that they are approved in Europe in stricter conditions due to the known critical safety concerns they pose. These substances can only be authorised by Member States in pesticide products when alternatives don’t exist. This substitution must take place whenever a safer chemical or non-chemical method, safer for human health and the environment and with similar effect, can be used on the crops.

The snag is that the substitution requirement was never enforced by Member States, which authorised Dimoxystrobin, Ipconazole and Oxamyl as any other substances (read more on substitution here). Yet, implementing these legally required substitution rules could be a game changer in terms of human and environmental protection.

Read more:

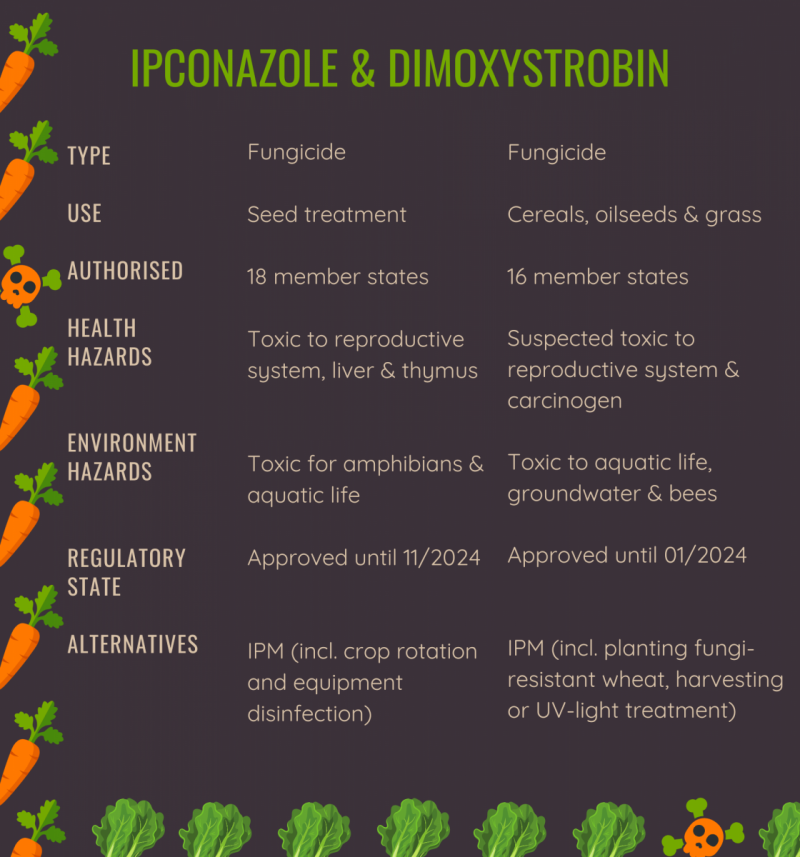

- Factsheet on Dimoxystrobin

- Factsheet on Ipconazole

- Factsheet: Patterns of systematic and unlawful prolongation of toxic pesticide approvals by the European Commission

- Press release: PAN Europe takes legal action against systematic prolongation of permits for toxic pesticides' by the European Commission

- Homepage: the Toxic 12 Campaign

Notes:

(1) In these cases, Hungary in the case of Dimoxystrobin; France and Italy in the case of Oxamyl.