The European Commission will present a proposal for a new Pesticide Reduction Regulation on 23 March 2022. That will be the start of a discussion with the European Parliament and the member states. It will lead to important discussions in all EU countries that should not be dominated by the lobbyists for the industrial farming model. This discussion will have a profound effect on our health, nature, clean water, healthy soils and the path towards a more resilient agriculture. The regulation - once agreed on - will replace the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive that has been in place since 2009. This directive gave a clear path away from pesticides. It explains that non-chemical alternatives should be given priority and that synthetic pesticides should be used only as a last resort. It also aimed to phase out the most toxic pesticides. However, the regulation was hardly implemented by EU member states and not much changed in the use of pesticides. The new regulation could be a step forward if it would clearly address the key issues. In this position paper we highlight 10 important action points that need to be included to make it a success and help to improve food security, restore biodiversity and protect our health and environment.

Download the Position Paper in English here.

Download the Position Paper in Italian here.

In the frame of the revision of the Sustainable Use of Pesticides, PAN Europe advocates for:

- A regulation rather than a directive.

- A change in title: the Pesticide reduction regulation.

- A change in paradigm: synthetic pesticides should become the exception rather than the norm.

- A clear definition of what Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is…and is not!

- High-level IPM rules to become mandatory to receive CAP subsidies.

- Including environmental indicators in the 50% reduction objective from the Commission.

- Phasing out 100% of the more toxic pesticides by 2030, not just 50%.

- Phasing out pesticide residues in food.

- Banning synthetic pesticides in public spaces and for private use.

- Including the food chain in the process.

Introduction

In May 2020, the European Commission published the Farm-to-Fork and Biodiversity Strategies in the frame of the European Green Deal. Both Strategies establish pesticide reduction targets in order to produce food in a more sustainable way as well as to halt the decline of biodiversity and allow for its restoration. The European Commission aims at reducing the overall use and risk of pesticides by 50% until 2030 while the use of the more toxic pesticides shall be cut by 50% until 2030. With these strategies, for the first time in its History, and after years of advocacy by civil society as well as thousands of scientific publications, the European Commission is finally breaking a political taboo and expresses its will to set pesticide reduction targets.

While the acknowledgment that pesticides are a major issue constitutes a major political progress on the Commission side, implementing the Commission proposal would simply mean 'finally doing what is already in EU law since 2009'. PAN Europe welcomes the idea to define mandatory pesticide reduction targets at both EU- and national-level. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that both objectives should have already been reached, would Member States and the Commission have implemented existing EU legislation.

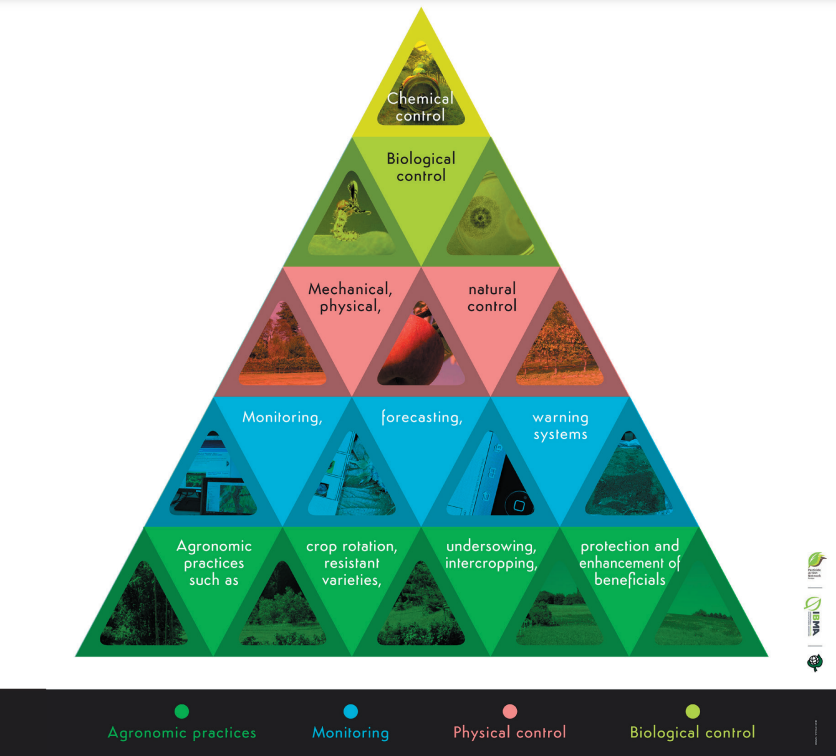

Indeed, according to the Directive on the Sustainable Use of Pesticides (directive 128/2009/EC, here after 'SUD'), EU farmers are to implement Integrated Pest Management (IPM) since 2014. The directive clearly explains that non-chemical alternatives should be given priority and that synthetic pesticides should be used as a last resort.

In the same vein, the more toxic pesticides' should have been removed from national markets already, were the pesticides regulation 1107/2009/EC correctly implemented by the Member States. Indeed, a list of the most toxic pesticide active substances (Candidates for Substitution list) has been established. According to the regulation, since 2011, Member States were not supposed to grant national authorisations when either ‘safer’ chemical and non-chemical regulated or non-regulated alternatives exist.

In both cases, Member States have failed or deliberately refused to implement EU-legislation, giving priority to a model of intensive agriculture, while the European Commission has failed to make sure that Member States gradually reduced the use of synthetic pesticides and stopped authorising the most hazardous ones. PAN Europe welcomes the move from the European Commission to finally protect citizens' health and the environment.

After more than 10 years of inaction both at Member States and EU-level to ensure pesticides' use reduction, PAN Europe considers that stricter rules are needed with clear objectives and responsibilities.

More and more publications[1] point at the fact that feeding the EU without pesticides is at arm's length and that farming without pesticides increases the profitability of EU farms. At the same time, a recent study[2] highlights the considerable and unacceptable costs of pesticide use, both for the communities as well as for farmers themselves. Considering the strategic importance for the EU to ensure its own food supply, and considering the major threats posed by climate change, the crisis of biodiversity as well as the growing number of chronic health diseases related to pesticides exposure[3], it is of major importance that the EU maintains a diversity of farms that enable the production of healthy food while allowing biodiversity to recover. Therefore, a major shift in mentality must take place, in order to move away from a system where higher yields is considered a positive indicator, without any consideration of the inputs and external costs, but rather put forward farms’ sustainability, be it in terms of farmers’ profitability or environmental recovery. Contrary to scaremongering messages disseminated by the agrochemical industry, lower yields does not mean going hungry or importing more food: our current food system leads to massive losses of food due to long chains or sometimes overproduction.

The important development of organic farming as well as the numerous examples of farmers implementing true IPM and considerably reducing their use of pesticides, showcase that today one cannot question the possibility of a transition towards pesticide-free agriculture anymore. Some sectors are very advanced in some regions, e.g. the wine sector abandoning 100% of insecticides in Luxembourg while Sweden decided in the 80's to work without any soil fumigant. The transition is just a matter of political will.

Citizens' are demanding such a change. On the one hand, already 2 European Citizen's Initiatives (ECIs) addressing pesticides issues, have been successful in collecting each over 1 million signatures. Out of 7 successful ECIs[4], in a total of 111 launched initiatives, 2 of them ask for a phasing out of pesticides. This major democratic signal cannot remain unheard.

In addition, EU Barometers regularly highlight that the foremost concerns of EU citizens regarding the quality of their food refer to contamination with pesticides while strongly reduction pesticide use was defined as an environmental priority in the Citizens Panel of the Conference for the Future of Europe[5].

Protests are regularly organised by citizens throughout the EU while pesticides are a source of tension between the farming community and citizens, beekeepers or conservation groups.

Finally, 35% of the EU budget is dedicated to the Common Agricultural Policy. From a democratic perspective, it is thus not acceptable to maintain a system where EU farming costs such a considerable amount of money, while the mainstream type of agriculture endangers citizens’ health and the environment. In addition, instead of supporting the production of healthy food in a sustainable way, an important part of the CAP budget ends up reinforcing the strength of agrochemical companies on the back of citizens. The 'Public money for public good' principle must be implemented and progress towards pesticide reduction must be linked to public financial support.

More than defining specific targets and deadlines, the revision of the SUD is an opportunity to set a clear direction for EU agriculture. It is a chance for the European Commission and Member States to take over the control of our food systems, so that food is considered as food again, a public good, and not as a commodity. Since the green revolution, the number and diversity of farms has collapsed, agricultural land has been abandoned due to erosion, and soils have been considerably damaged by the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. In order to ensure the long-term production of our food, the EU needs to move away from chemistry and develop healthy and productive agroecosystems.

The present position paper presents what Pesticide Action Network Europe considers needs to be modified to the SUD in order to finally allow EU agriculture to initiate a transition towards its independence from agrochemicals.

I. A frame to free farmers from pesticides

Pesticides represent a considerable cost for farmers. Increasing productivity with chemical fertilizers, using hyper-productive crop varieties grown on impoverished land leads to weakened plants that need pesticides to remain productive. The race to productivity needs to be replaced by improving farm profitability and sustainability.

To move away from synthetic pesticide dependent farming systems, we see two ways: put in place high-level IPM programmes in EU-farms and extend organic agriculture. Boths organic farming and IPM are knowledge-intensive and require experience and advice. While for organic agriculture, specific legislation with clear definitions and exclusions exists, IPM is still not adequately defined/covered. IPM should not be seen as a final goal or label, but rather as an iterative process that enables constant improvement, and a capacity of EU farms to become adaptable and resilient. While it provides farmers benefits in terms of reduced pesticides costs in the long run, the transition towards agroecology must be accompanied.

1. Defining what IPM is…and is not

A clear definition of IPM must be set in the new legislation. PAN Europe recommends the following definition: "Integrated Pest Management is an iterative process that places preventative agronomic measures at the heart of agricultural plant production's pest control. When these fail, cultural practices and physical pest treatment is favoured, before using biocontrol and, as a last resort, chemical alternatives can be used".

While the definition of IPM should be simple and clear, a set of mandatory basic practices should be fixed at EU-level. Each Member State should go further and fix additional mandatory crop-specific IPM requirements, relevant for their pedoclimatic and pest conditions. PAN Europe suggests to make the following practices mandatory at EU-level:

- A minimum 5-year crop rotation for arable farming and annual field vegetables.

- Make use of robust and/or resistant varieties[6].

- Inter-cropping, cover crops and mixed cropping in arable crops.

- Only crops and varieties that can be grown organically at national- or regional-level should be allowed[7].

- For all crops for which mechanical/physical weeding is available, herbicides should be banned.

The revised legislation should also very clearly define what IPM is not. In particular, preventative use of pesticides should be banned. PAN Europe suggests the following practices to be banned from the EU:

- Treating seeds with synthetic pesticides, as well as synthetic pesticide granules when sowing the seeds.

- Use of soil fumigant and other soil treatments.

- Calendar-based pesticide spraying.

- Aerial spraying with synthetic pesticides, including the use of drones (no derogations allowed).

- Use of synthetic pesticides on grassland.

- Use of GMOs and so-called New Breeding Techniques.

2. Defining IPM guidelines at national- or regional level

Mandatory IPM guidelines should be defined at national- or regional-levels for the crops representing at least 95% of the cultivated land, nationally or regionally. Such guidelines should constitute the minimum level of IPM farmers should legally follow. Not following such guidelines should immediately lead to strong reductions in farmers’ CAP subsidies.

Guidelines should be revised on a yearly basis, based on the input from farmers and agronomists from the national/regional IPM programme and should become stricter over time, in order to gradually shift practices from a chemical-intensive agriculture towards a knowledge-based agroecological agriculture. The improvements in such guidelines should be linked to the pesticide-reduction targets.

3. Establishing IPM implementation plans at farm-level and accompanying the transition

An IPM implementation plan should be established on each farm, based on where the farm stands in terms of IPM practices. State-funded programmes shall be developed to train agronomists to implement such plans and adapt to the local context. The development of such plans shall be free of charge for the farmer and a system shall be put in place in case the farmers need rapid advice.

An IPM record file should be completed by farmers. It should contain any practice linked to pest control, be it preventive or curative. States and regions should develop a standardised and easy to use system that enables farmers to report on a yearly basis on a series of indicators (e.g. preventative measures taken, non-chemical alternatives used, monitoring, use of pesticides, etc.).

In all cases, the use of synthetic pesticides must be documented (product, application rate, quantity, production type) and duly justified: only when available preventative measures have been put in place, can a farmer make use of a synthetic pesticide.

In the long run, PAN Europe considers that pesticides should be treated as antibiotics: their use should be strongly regulated and limited to cases where truly necessary with a prescription system by an independent agronomist.

4. Forbidding industry-funded advise and any kind of advertisement

In order to ensure a transition towards low-input farming, it is of utmost importance to suppress the influence of the agrochemical industry on farmers. The pesticide industry should be prohibited from providing any kind of direct advice or having any contact with farmers. In the same vein, advertisements of pesticides shall be banned in any format - like it is for medicines under prescription or for tobacco.

II. Mandatory pesticide reduction targets

1. Reducing the use and risk of pesticides by 50%

Before the absence of implementation of the SUD by the Member States, setting mandatory pesticide reduction targets at national-level cannot be avoided.

Based on the experience from farmers putting in place IPM, PAN Europe considers that the 50% reduction objectives of the Farm-to-Fork Strategy is, from an agronomic perspective, not very ambitious. PAN Europe considers the European Commission should have aligned on the demands of the Save Bees and Farmers ECI, meaning an 80% reduction by 2030.

Furthermore, by including the notion of risk and making use of Harmonised Risk Indicator 1 (HRI1)[8] the European Commission is reducing even more the level of ambition of its Strategy. Indeed, a series of pesticide approvals are currently under revision at EU-level and they will most probably be removed from the market in the coming years due to their excessive toxicity. This will automatically lower the 'use and risk', while no change in practices at field level will take place. Furthermore, HRI1 was developed based on human toxicity indicators only - excluding pesticides' environmental impact - and it does not include the numerous derogations provided by Member States in order to make use of highly toxic, and often banned pesticides. This will distort the evaluation of the progress made in the EU. The European Commission should revise its indicator system (HRI1 for use should include environmental toxicity, while HRI2, that measures derogations in Member States, should be included in the overall counting of the 50% reduction). HRI1 should be either strongly improved or the notion of risk in the 50% reduction target should simply be abandoned.

PAN Europe considers that the establishment of a mandatory 50% reduction objective for all Member States is required. The situation in all 27 Member States is very different. Indeed, a few Member States are more advanced in terms of IPM or organic agriculture than others, while some Member States do not authorise the more toxic pesticides and others do.

While the frontrunners might consider they are halfway towards real IPM, the knowledge developed by farmers should also be seen as an advantage that less advanced countries do not have.

In the same way, countries authorising a lot of highly toxic pesticides might consider that banning a few will help them reach the 50% target easily by reducing the risk without changing the use. This might be true but their farmers will still need to adapt and acquire the necessary knowledge to start implementing IPM and working with less toxic substances.

We, therefore, consider that a mandatory 50% reduction target should be set for each Member State, taking as a baseline the average uses over the 3 years preceding the implementation of the new legislation. No derogation should be given to derive from such a target.

2. Banning the more toxic substances

The more toxic substances, covered by the second reduction target, should normally already been dealt with by the pesticides regulation. Indeed, article 50 of regulation 1107/2009/EC gives Member States the obligation to restrict national authorisations of Plant Protection Products containing a Candidate for Substitution to cases where no alternative exists. Where such alternatives exist, these substances should be substituted.

Crops on which the more toxic substances are used are also grown in organic agriculture. This leaves no doubt to the fact that non-chemical alternatives exist and to the enforceability of these substitution provisions. Yet the use of these more toxic substances has never been reduced by the Member States. The root cause of this failing system is that Member States and the European Commission have agreed on a flawed Guidance Document that gives priority to having many chemical alternatives while disregarding efficient non-chemical alternatives. This document, which was captured by the pesticide industry, must independently be revised in order to meet the objective of regulation 1107/2009/EC: ensure a high level of protection of human health and the environment. Indeed, a strict implementation of the law would have led to a ban on these more toxic substances, since regulation 1107/2009 has entered into force 11 years ago (2011)!

Therefore, the objective to ban 50% of the more toxic pesticides is not sufficient and scopes article 50 of regulation 1107/2009/EC. PAN Europe advocates in addition for the new legislation to contain an article obliging Member States to include in their National Action Plan a binding revision plan of all the national authorisations containing candidates for substitution. By 2030, all the authorisations for which a non-chemical alternative exists should be withdrawn and substitution implemented.

3. Gradually banning pesticide residues in food

One aim of the SUD being to protect citizens against exposure to pesticides, the revised legislation should ensure that citizens should not be exposed to pesticides through the food they eat. PAN Europe advocates that strict residue limitations are gradually put in place, in order to protect people's health and to incentivise farmers to modify their practices.

The revised legislation should establish a plan so that by 2030, residues of pesticides would not be allowed anymore in food and feed produced in the EU. MRLs would then be reduced to the limit of detection. Identical rules would apply to imported food and feed to put EU farmers on a level-playing field.

PAN Europe advocates for allowing a maximum of 3 synthetic pesticide residues in food and feed the year after the implementation of the revised legislation. A calendar to lead to 0 residues by 2030 should be put in place.

III. Banning pesticides in public areas

While in some countries such as France and Belgium the use of synthetic pesticides has been banned in public areas years ago, through a proper implementation of the SUD, it is unacceptable to see that in many Member States, pesticides keep being used in or close to children playgrounds, in sideways, parks and other so-called specific areas. The use of pesticides in close proximity to residential and recreation areas represent major routes of exposure for citizens and should be banned at once.

PAN Europe asks for the revised legislation to impose a ban on the use of synthetic pesticides in public areas from 2025. Some Member States have extensive experience in managing public spaces without pesticides. This should be the basis for spreading good practices throughout the EU, hence leaving more space to nature while protecting people's health, in particular, that of the most vulnerable.

IV. Banning pesticides for non-agricultural private uses

The use of pesticides by non-professionals and their use in non-agricultural private properties are major routes of human exposure and lead to the destruction of biodiversity. Such practices must thus be banned as soon as the new legislation is published.

Some countries such as France and Belgium have already banned the use of pesticides in non-agricultural areas. These countries should serve as an example for the Member States that are less advanced.

V. Incentivising the change

As mentioned previously, IPM is knowledge-intensive. It requires systemic changes at the level of the farm, which needs public support. On the other hand, the farming sector is massively financially supported by the EU and the European Commission must make sure that EU farmers comply with the rules. The Farm-to-Fork objective has not been introduced in the future CAP legislation, which was a major mistake.

However, up to now, despite the fact that a minority of EU farms properly implements IPM in a manner that leads to a gradual reduction in the use of pesticides, no system of financial penalty was put in place in order to incentivise farmers to develop a proper IPM plan and to implement the 'Public money for public good' principle.

Therefore, a link must be established between the revised SUD legislation and national CAP Strategic Plans, making sure that CAP money is tied to farmers’ full implementation of the revised SUD legislation and to effective reductions in pesticide use.

Furthermore, Member States should be allowed to financially reward farmers in their efforts to move away from pesticides.

VI. Retailers and supermarkets, major actors of change

The systemic change needed to move away from pesticides concerns farmers but not only. Indeed, a major driver of the significant use of pesticides is the food chain and its demands. Apples need to look perfect, hence a massive use of fungicides to avoid any scab spot on the peal, while potatoes should contain no trace of wireworms, hence the massive use of soil fumigants and other soil insecticides in potatoes growing. Both examples show how big a responsibility the food chain has on the massive use of pesticides.

In order to include the food chain in the effort to move away from pesticides, food processing companies, retailers and supermarkets' guidelines must be adapted. Otherwise, the burden to cut pesticide use will be put on the shoulders of the farmers while the level of requirement in terms of aesthetics or yields could remain the same at the level of the food industry, which would be unfair.

PAN Europe considers that in case retailers or supermarkets are in contract with farmers for specific productions, the IPM mandatory rules set at EU- and national-levels should be part of the contract. In that respect, both retailers/supermarkets and farmers under contract would be bound to take part in the transition towards less pesticides.

A system should thus be put in place to ensure that the food chain becomes an actor of the reduction in pesticides rather than a break to any improvement. The food chain should contribute to the yearly reporting to public authorities about quantities of pesticides that were used to produce the food they process and about progress in the implementation of high-level IPM.

VII. Protecting people and biodiversity

Since its publication in 2009, the SUD has massively failed to protect citizens against the health risk of pesticide exposure. Academic studies, as well as citizen science studies, have demonstrated that people are massively exposed to pesticides. On a regular basis, the European Commission and Member States ban pesticides that have been used for decades because enough evidence shows they are linked to chronic diseases such as cancers or infertility. This will most probably be the case for dozens of today approved pesticides.

For this reason, it is of major importance the revised legislation puts an emphasis on the protection of citizens' health.

In the same vein, biodiversity is collapsing worldwide and scientific research has pointed at intensive agriculture, and in particular the use of pesticides, as the main drivers of such a man-made disaster.

The restoration of biodiversity is a key element of the EU Green Deal. Agricultural land is currently a vector of the decline of biodiversity and acts mostly as a biodiversity sink. Indeed, whatever protection measures are taken next to agricultural land to restore biodiversity, the massive destruction of life through the use of pesticides will strongly reduce any policy meant to increase biodiversity.

A striking example is the setting of buffer strips around fields, in the frame of agri-environmental measures from the current CAP. Attracting beneficial insects in flowering strips that in turn will be exposed to drifts of insecticides does not make sense. Public money is used to attract beneficial insects that are then exterminated. Coherence is needed.

PAN Europe considers that a mandatory minimum non-sprayed buffer zone should be put in place throughout the EU:

- 50m buffer zone next to private and public properties, roads and paths as well as watercourses.

- 25m buffer zone next to fields from a neighbouring farm.

Furthermore, the restoration of biodiversity must be given immediate priority in natural areas. Natura 2000, nature reserves as well as national parks. Once more, supporting such structures financially while maintaining the use of pesticides does not make sense and is a waste of taxpayers' money!

VIII. A regulation rather than a directive, the necessity to put in place strong incentives for Member States

Before the inaction of Member States since 2009 and before the blatant lack of will of many, PAN Europe considers that a regulation would be more appropriate than a directive. It would put all Member States on a level-playing field at once and allow for an easier and quicker monitoring of the situation by the European Commission.

Furthermore, before the urgency to speed up the transition towards agroecology, as well as a better implementation of pesticide authorisation rules (regulation 1107/2009), PAN Europe considers that strong incentive measures are needed at Member States' level. Linking the future legislation to CAP funding is a prerequisite to the success of the future legislation. If Member States fail to reduce pesticide use, a significant reduction in CAP subsidies should be the consequence. In case Member States fail to meet their target 1-2 years after the deadline, the European Commission should be very clear that it will sue them before the Court of Justice of the EU. Indeed, in terms of pesticides, many Member States are used not to respect EU law and the European Commission does not launch infringement procedures while, as the guardian of the treaties, it should.

IX. A new Title for a real change

As broadly acknowledged by the European Commission now, synthetic pesticides present a risk for people's health and biodiversity. Scientific evidence does not support the idea that the use of synthetic pesticides in EU agriculture can be sustainable. In this regard, it does not make sense to maintain the same name: it gives an impression that the environmental risk and hazard posed by pesticides are manageable while evidence shows they are not.

The title should clearly reflect that the objective is to reduce synthetic pesticides to a minimum. In that regard, PAN Europe considers that the revised legislation should not be called the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation but rather the 'Pesticide reduction regulation'.

Notes:

[1] The economic potential of agroecology: Empirical evidence from Europe, Vanderploeg et al., 2019 // An agroecological Europe in 2050: multifunctional agriculture for healthy eating, IDDRI, 2018.

[2] Pesticides: a Model that’s costing us dearly, Basic, 2018.

[3] Among others, cancer, the decrease of fertility or Parkinson disease have been linked to pesticide exposure.

[4] The Save Bees and Farmers ECI is currently in the process of validation but as it collected 1.18 million signatures, mostly online, the organisers consider it will succeed in having more than 1 million validated signatures.

[6] A list is to be established by each Member State, in agreement with the European Commission.

[7] Growing a crop or a variety that is not adapted to the local pedoclimatic/pest conditions leads to diseases and need of chemical treatments.

[8] Harmonised risk indicators: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plants/pesticides/sustainable-use-pesticides/h....